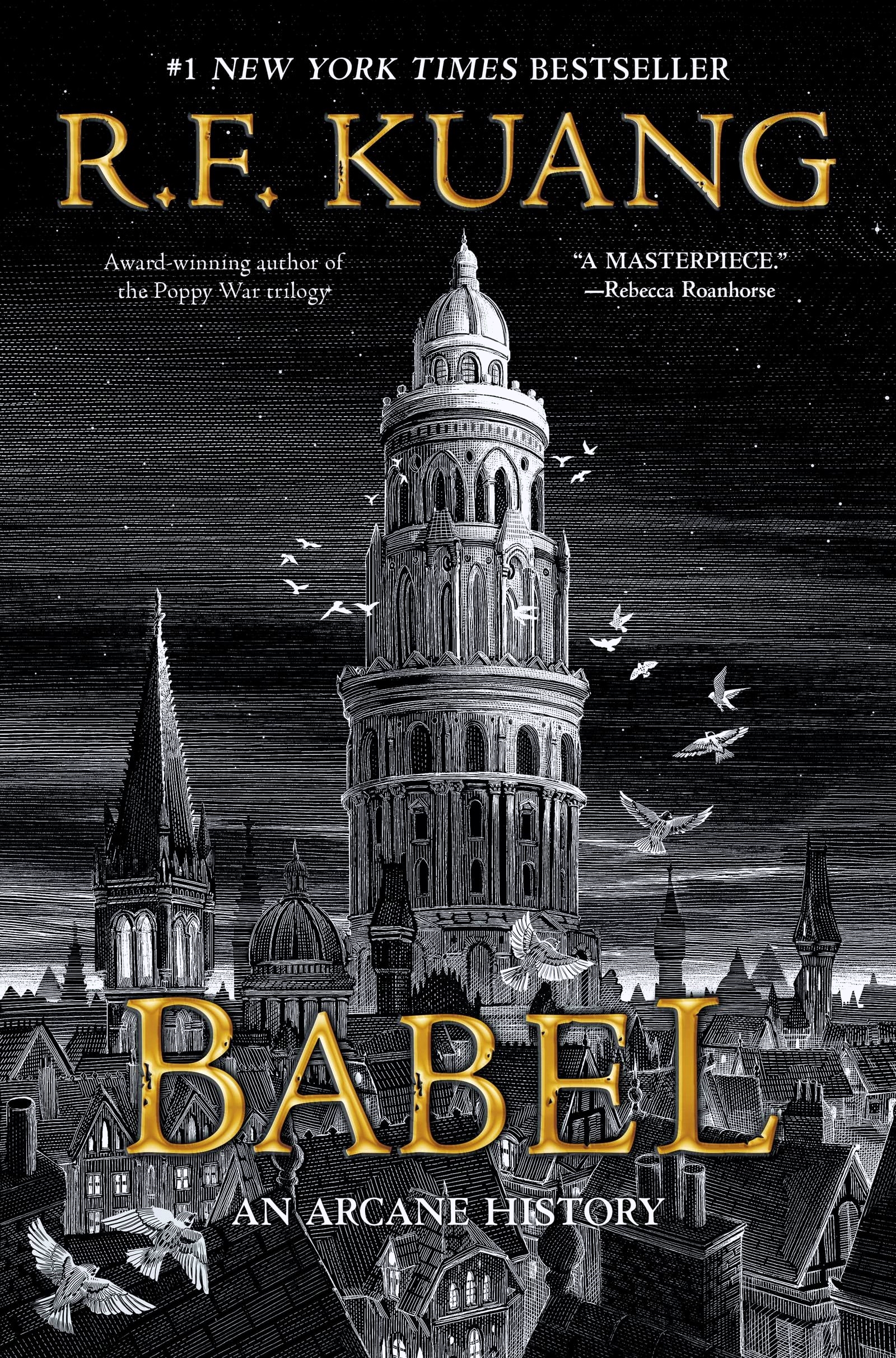

I found The Poppy War trilogy to be a flawed, but fun series. I initially wasn’t planning on reading ‘Babel.’ But then this book was nominated for/won a ton of awards, and I got curious. I decided to give this a try despite my misgivings.

I found ‘Babel’ frustrating. At moments, I enjoyed this book more than I did Poppy War, but at other moments I disliked this book more than Poppy War.

If I were to describe my relationship with Kuang’s work, I’d say she’s one of my favorite authors for her conceptual work, but I don’t find these books spellbinding. I found myself skimming through parts of this due to lack of enjoyment. On the other hand, her books give me a chance to do research and reflect on history, which is something no other working author really gives me a chance to do. I really love doing in-depth reviews like this.

I’m going to explain my negative (and positive!) thoughts on this work of art. This was a challenging work of art which demands being taken seriously. Spoilers Below. I’m writing this review in good faith, as one author reviewing another’s book, trying to balance positives with negatives. As part of my preparation for reading this, I listened to 2 thirty hour long lecture series on both the British Empire, and also the Chinese Empire of this era.

WHAT IS THE TARGET AUDIENCE? WHAT GENRES? WHAT MAJOR TROPES?

- 16+ years old

- Decolonialist fiction

- BIPOC (Both author and subject matter)

- Interrogating the guilt within the Western intellectual system, and how universities can be objects of oppression.

- The British Empire of the 1830’s-1840’s

- The Chinese poppy wars

WARNING! QUIT READING NOW UNTIL YOU FINISH READING THE BOOK! SPOILERS!

Audiences received this book with some level of controversy. This book is about racism, and I’ve seen some book reviewers say this book was bad due to how didactic this book is. No minority artist or author should feel compelled to coddle the emotions of the majority in their art. The white majority were once gatekeepers for art; only recently have minority populations gathered enough wealth and power to make art for themselves. Perhaps the author wrote ‘Babel’ for primarily a minority audience, and it was written to vent about how unjust the white Western world is for nonwhites. As a work of art, this book is valid.

Okay, with that necessary preamble done with, let’s start.

BIASES STATED

I read ~20 book reviews describing ‘Babel’ before reading this, both positive and negative. I do this with most books I read. In this case, I think it colored my opinion on this book in a negative way. HOWEVER, after reading this I do think a lot of the negative reviewers weren’t willing to meet this book halfway. This is better than a lot of negative reviews say it is.

CONCEPT AND EXECUTION

This book’s concept is the lifestory of a young man who’s caught between two worlds: that of a young citizen of the British Empire who loves the products and glamour of the empire, and the oppressed colonies of that Empire which are exploited for wealth. It takes place in Oxford, a university setting where scholars utilize magic to create the Industrial Revolution. It also takes place in Canton China, where the IRL Poppy War is going on. The protagonist is biracial, half English half Chinese, and is forced to pick a side. Good concept.

I did not enjoy this book’s execution. This book is dry as salt. A lot of this book is narrative exposition, either through the medium of dialogue or straight textual blathering. As a fantasy fan, I can tolerate infodumps and blather, but this was too much for me. As a fantasy fan, I enjoy some amount of adventure in my novels; this book lacked that sense of adventure one expects in the genre.

Now for a weird hot take: this had a similar vibe to the ‘Cradle’ books. Specifically, in the world of ‘Cradle,’ every person’s entire life revolves around leveling up by chi cycling. There are no farmers, no weavers, no plumbers; near as I can tell, everyone chi cycles as their dayjob. Every aspect of the plot and setting ultimately orbits around levelling up. ‘Cradle’ are fun books, but this setting feels unnatural.

In ‘Babel,’ every scene, character interaction, and aspect of the worldbuilding ultimately orbits the concepts of racism and colonialism. You can’t escape this worldbuilding because it colors the entire setting and story. This setting feels unnatural.

Now, it’s okay to tell an instructive story about racism. But this got long in the tooth. I feel like there was a sharp 250 page book in this which got muddled within a 550 page book. The didactic nature of this story would have worked in a shorter text.

FFS, I am a scholar myself; I read one or two nonfiction books a week. Reading a book about a booknerd should be within my wheelhouse. Something about this book went horribly wrong if I didn’t like it.

CHARACTERS AND CHARACTERIZATION

EDIT: I’ve gotten some pushback, so I’ll explain myself further.

Actors for cinema and actors for theater employ different acting styles; in cinema, actors emote for the camera, which is usually nearby, while in theater, actors emote for the member of the audience who is farthest away from the stage. Simply put, it’s hard for that most-distant member of the audience to read the body language of the actors, so the actors ham it up to make sure that people who are far away can tell what’s going on. For cinema, an actor might just raise an eyebrow to get a point across; in theater, an actor might gesticulate wildly to get that same point across.

The characters in ‘Babel’ are theatrical. They behave in blunt and obvious ways, so the most-distant member of the audience can understand what’s going on. It was a deliberate narrative choice by the author to have the characters be over-the-top, for the purpose of getting the message across. I personally did not enjoy this style; as a reader, I’m not sitting in that most-distant chair. I found it verging on camp, stylized to the point of breaking my suspension of disbelief. This book was ‘realistic;’ therefore, having ‘unrealistic’ characters broke my suspension of disbelief.

Back to the original review.

I’ve been reading reviews for ‘Babel,’ and a common criticism is that all the white characters are some shade of antagonistic: from unlikeable, to just evil. I think there is a seed of truth to the complaint.

In this book, (forgive my crude language) the English sniff their own farts; only the protagonists are smart enough to smell the fresh air. The one English protagonist, Letty, betrays the other protagonists by the end of the book. The white English do some heinous shit throughout the novel. The message is clear, and this is very much a message book: white people are evil.

Giving the author the benefit of the doubt, perhaps the goal was deliberately invoking cognitive dissonance in white readers. All people view themselves as the hero of their own story, therefore when a white person reads this book they might feel cognitive dissonance. That cognitive dissonance was how the author sought to discuss racism. If so, this book did a mediocre job exploring racism as a topic.

Let’s now dive into the heart of the issue: Letty. I genuinely liked her as a story mechanism. The author set out to explore the failures of moderatism. To paraphrase Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, ‘The enemy of reform is not the unapologetic racist, but the squishy moderate.’ Letty is a squishy moderate, according to this description. The author more or less directly pointed out that Letty was at best a performative ally; she leaves Hermes the moment she would be forced to make a sacrifice for her beliefs. As a mechanism of the story and a manifestation of historical forces, Letty worked.

But Letty also served to undermine the story at hand. This book bungled the execution of the message by having Letty betray the heroes. By having the one white protagonist being the twist villain, it is easy to interpret the subtext of the story as saying ‘you can’t trust those shifty white people’ even as the printed text of the book says ‘Letty betrayed us because she was protecting her family and her wealth (and also because Ramy dumped her).’

(BTW, some reviews about this book complain that ‘all white people are evil’ in this book. This subtext of ‘shifty white people’ is what so many reviewers are complaining about. More on subtext and show-don’t-tell later.)

The author’s goal with Letty’s betrayal was saying ‘the system maintains itself through the passive acceptance of the middle classes, and the active betrayal of moderates’. If we were to re-write the book, how can we maintain that message but at the same time get rid of the subtext?

I’d suggest we add another character.

Let’s talk about the Irish Potato Famine. The famine happened because the English weren’t willing to invest in agricultural reforms in their Irish colony, even though they did reform English farms; the English would rather keep Ireland a provincial backwater. As a result, the potato blight hit HARD. I’m leaving out some nuance, but you get the point: because of English neglect, a million people died of starvation.

This example of English colonialism was sitting one island over from this book and it was never discussed. The Irish Potato Famine began in 1845, while the First Opium War ended in 1842; this topic was fair game for ‘Babel’ to discuss. If this story brought the Famine up, it really would have proved the book’s point. In my opinion, ‘Babel’ examined the narrative of colonialism and racism through the obvious lens of ‘whites vs nonwhites.’ Today, we feel cognitive dissonance when talking about the Irish not being counted of the white race. The narrative could have weaponized this cognitive dissonance to prove a point.

(If you are interested in reading books exploring this topic, I suggest you check out Mary Robinette Kowal’s ‘Glamourist Histories’ series. That series touches on English racism and classism during this era.)

Let’s talk about the characters in general now.

When I spoke about Letty above, I commented that I liked how she served as a manifestation of historical forces. Many of the characters in this book seemed to primarily exist to serve the narrative function of conveying ideology from the author to the reader… as opposed to, you know, being a character, with thoughts, quirks, secret passions, embarrassing secrets.

Expository characters are not a bad thing innately; if you go back and read stuff by the early greats like Asimov or Heinlein, they weren’t exactly famous for writing gloriously nuanced characters. The early greats used characters to exposit sci-fi concepts. ‘Babel’ used characters to exposit fantasy and colonialism concepts. That’s fine, not all books have to be written in the style of super-deep, psychologically driven characters. I give this a passing grade.

SETTING AND WORLDBUILDING

I enjoyed the segments where the characters learned about the magic system/linguistics. I am a giant nerd about… well, everything, linguistics included. If you want to learn more about linguistics, I suggest you check out the youtube channels NativLang and Connor Quimby. I’ve listened to them for years, and they’re good. This book did a fun job exploring the topic.

I felt that the author did A REALLY REALLY GOOD JOB of integrating the theme of using minorities to exploit minorities. The author’s idea for the tower of Babel is just genius. The British Empire brings in impressionable youths into the tower and uses their skill in linguistics to control and oppress the people they originally came from. This interweaving of plot, magic system and setting was deft and clever and thematically rich. The magic system of the Babel translation school is literally colonialism given a magic wand.

The magic system itself was clever and cool; I wish it was featured more.

Why silver? It’s because of tea.

Back in this era, Britain got their tea from China. However, the British Empire had a policy that exports must be greater than imports, and they would be paid in silver to make up the difference- this is called Mercantilism. (To summarize mercantilism, it means: “Free trade for me, but not for thee.”) The problem was that the British liked tea so much that the flow of silver went in the direction of China, not the other way around. So, because of the official policy of Mercantilism, the British had to make up the difference between imports and exports. China were isolationist, so they refused to import anything; therefore the British had to smuggle exports into China to balance the checkbook. And if you’re going to smuggle something, it needs to be expensive per unit weight, have a high demand and tradeable on the black market to be worth the time and effort… thus, opium.

Therefore silver=opium.

(Adding a small hype moment here, this book hammered on Adam Smith and Free Trade, which I really liked. It made the British look like hypocrites.)

By using silver as the basis of this magic, the author is thematically including this bit of lore in with the rest of the story. Robin exemplifies the British method of colonial control: the British East India Company takes silver out of China; the tower of Babel teaches the foreign students from colonized places like China to create magics to benefit the British colonial project using silver extracted from China. In this way, the British Empire uses the products of its colonies to oppress its colonies. It’s an ouroboros, a snake eating its own tail. Great theme/motif work. This reflects how in the real world, the British used Indian sepoy troops to oppress India, or turned Protestant Christians against Catholic Christians in Ireland. While colonial populations fight amongst themselves, Britain extracts wealth.

And now the bad: the author took the most blunt way about telling this story, and it cost the story severely.

Britain in the real world poppy wars were SUPER morally evil. Indeed, the real world events this story were based on are so comically evil that this book comes off as comically simplified. Does that make sense? You can’t tell a subtle, nuanced story when narcostates are involved, because narcostates are evil. That was the point that the author was making, that Britain was evil when it dumped opium in China. And yet because the author accurately portrayed evil as evil, many readers who read the book and said ‘no duh evil is evil. This book is obvious and boring.’

When reading reviews for this book, I’ve noticed a common refrain. To summarize, a lot of people felt that the author was heavy handed with her social critiques. They think the narrative preached its message. We live in a jaded age; when confronted with obvious political speech, a lot of people bounce right off it. I think something like that happened here.

I think two things were the main obstacles to this book reaching that jaded audience:

- The narrative approached the theme in the simplest, most blunt method possible.

- At every turn, Robin suffered the sins of racism and colonialism, and as the reader has empathy for Robin the reader gains understanding for why racism and colonialism are bad.

- Because this lacked subtlety, it got repetitive and boring. That might be the narrative mechanism the author was going for, to show to the reader that minorities are constantly assaulted by discrimination daily. The author was trying to make the reader feel that constant assault. But it still is a repetitive narrative mechanism, and that which is repetitive becomes boring.

- The antagonists were all strawmen, twirly mustache evildoer types.

- They were all bluntly evil racists. Because it was all so blunt, it felt like the author was talking down to the audience, like the narrative didn’t trust the reader to come to our own conclusions about the ethics of racism.

- I don’t think the author intended to sound patronizing of the reader, but I think perceiving a patronizing attitude in the text is understandable given how blunt this book is about everything.

So the author is between a rock and a hard place. Either accurately portray history as being racist and evil, and consequently write a book which readers view as being blunt. Or tone down the racism and evil and not write an accurate book.

I think the author was justified being blunt. The author tried to directly tackle the drug trade and came off as preachy as a result because you can’t say ‘there’s two sides to every story’ about the drug trade and racism.

But still, this book didn’t work for a lot of good-faith readers, including me. I think the narrative could have been structured differently to appeal to those readers without losing the message. Here are my thoughts on the-roads-not-taken.

In the real world, the British Empire expanded using more than just opium diplomacy. Did you know that quinine was a weapon of war? The British used quinine to make their soldiers immune to malaria so they could invade India and Africa. Therefore, quinine was a tool of colonialism.

Back to ‘Babel’. Now imagine if the book started with small, subtle acts of unjust colonialism and escalated slowly. Instead of opium, start with quinine. The British characters in this book can say, “Colonialism is good. We brought these natives quinine and now they live long, healthy lives free of malaria.” And the colonized characters in it can say “No, colonialism is evil. You’re using quinine to keep your army alive and oppress my people.” The reader then can think about the two arguments and decide for themselves: is the colonizer right, or the colonized? Should medicine be used as a weapon of empire at all? Then after this babystep, introduce Britain’s drug dealing opium.

What if Robin started the book completely gung-ho for the British Empire, and only slowly changed his mind as he faced more and more racism? Letty and Griffin could act as the angel and devil on Robin’s shoulder. Letty makes arguments like the one above about quinine. Robin starts the book agreeing with Letty, but slowly agrees with Griffin. The final swap happens when Robin returns to opium-addicted Canton and learns just how horrible imperialism can be. The book as-written has Robin and the crew all pretty much on the same page about the downsides of empire from the first page; writing it this other way would create a more dramatic character arc.

PLOT

Going back to what I said above, I feel like the author frequently took the most obvious solution for every problem.

This book is about racism, but basically only white-against-nonwhite racism. It barely touches the less obvious white-against-white racism, such as antisemitism or anti-Irish racism as examples. This book could have subverted expectations, while at the same time reinforced its points, by taking a more nuanced view of racism and exploring the topic fully.

Robin faces both macro and microagressions everyday in Britain. Yet when he returns to Canton at the 50% mark, he’s treated with respect by the local Chinese, in particular the ‘Handler of Barbarians’ dude. Wouldn’t it make sense if he was treated with racism back home in China? This book’s foundational worldbuilding is that racism is EVERYWHERE. Robin facing racism back in Canton would have subverted expectations, but at the same time doubled down on the foundational worldbuilding. He’s seen as Chinese in Britain; wouldn’t he be seen as British in China?

After Britain outlawed slavery in 1833, the Empire set up the West African Squadron of ships to patrol the coast of Africa and disrupt the slave trade. The West African Squadron saved 150,000 Africans from slavery. Britain didn’t profit off of this in any way; it was done for charity. In this case, the British Empire were actually heroes. It doesn’t make up for all the evil the Empire did, but this did happen. If the book referenced this it would have subverted expectations and humanized the British, despite their villainy. (Did the book talk about this, and I missed it?)

The primary villain in this book is the nebulous British Empire, and the narrative doesn’t make a good-faith attempt to humanize the villain. Everyone is the hero of their own story, even the British Empire. But this narrative was written with such a strong message of ‘Imperialism=Bad,’ that it ignores nuance to the real world story (e.g. the West African Squadron).

Speaking of imperialism, China is an Empire! Wouldn’t it have been neat if this book explored how China’s native colonialism and imperialism (for example the peasant uprising Taiping Rebellion), in light of the ideas this book was trying to examine? This would change the theme from the British being uniquely evil, to displaying the darkness native to all humanity. And given that this book is about racism, underscoring the common humanity between British and Chinese seems like a good idea.

Of the four main characters, it was Letty who betrayed the heroes to the British. I felt this was a cop out and obvious. It would have subverted expectations if Victorie or Ramy betrayed the heroes to the British. Let me explain:

- Thesis: Britain controls it’s colonies by using local proxies.

- Evidence:

- The British using Indian sepoy troops to control India.

- In Ireland, the British use Protestants to counter Catholics

- Robin (Chinese) is brought to Britain to benefit Britain at the expense of China. Likewise, Ramy is brought to Oxford to benefit Britain at the expense of India, and Victorie benefits Oxfords at the expense of Haiti.

- Conclusion: Ramy or Victorie betraying Hermes would restate the author’s thesis. I’d also be happy if Letty, Ramy and Victorie ALL betrayed Hermes together.

This book made obvious choices. It’s valid for a story to make obvious choices some of the time, or even most of the time. But a common bit of writing advice is that when an author faces a writing problem, to throw out the first solution to that problem because if it’s obvious to the author it’s probably obvious to the reader too.

One thing I liked about the plot, was how it ended. I liked how Robin makes the easy choice to die for his cause, while Victorie is forced to make the hard choice to live for hers, to struggle to survive, to escape at all costs. In the end, Robin was a coward. It was unassuming Victorie who was the real hero.

AUTHORIAL VOICE

The author herself cites that subtlety needn’t be a goal in and of itself when writing a book. I agree that subtlety needn’t be a goal in and of itself, but deciding not to use subtlety is like tying one hand behind your back before entering a fistfight. If you listen to her speaking in that link, I think she said she agreed with that position.

That said, the author writes blunt books with minimal intentional subtlety. However, subtext is still there, even if the author doesn’t intend it to be. The author neglects the battleground of subtext and subtlety, but readers will still read into subtext even if the author didn’t deliberately write any!

You know how I said that having the one white protagonist betray Hermes was a mistake? This is what I mean. That’s subtext right there. When people review this book and complain it uses the ‘stereotype of evil whites,’ they read the subtext and it’s right there.

(As an aside, is this stereotype the only way to interpret the subtext of this story? Of course not. But given how despicable the average English person in this story is, a reader seeing the subtext of the ‘stereotype of the evil whites’ is an understandable audience reaction.)

There’s a saying in writing circles that you should ‘show, don’t tell’ when you write. This means that an author should strive to demonstrate an aspect of plot or characterization through subtext as opposed to text.

This narrative doesn’t follow the methodology of ‘show don’t tell’ very often. Kuang is an author who uses themes/motifs of decolonialist literature. The ‘show don’t tell’ rule is a Western rule, originating during the Cold War and spread abroad as a method to counter the more didactic cultural communism literary tradition the Soviet Union was spreading. (I’m serious, that really happened.) Perhaps the author made the artistic choice to bring the decolonialist message into the storytelling itself. That’s good! ‘Tell, don’t show’ is a legitimate storytelling style.

… however, we readers are allowed to critique a book about things we don’t like, even if they are a legitimate storytelling style. Some people don’t like 2nd person fiction. Others don’t like Tolkien’s poems and songs. I dislike how flat this novel’s ‘tell, don’t show’ storytelling style is.

There is a middle ground between ‘tell, don’t show’ and ‘show, don’t tell.’ ‘Babel’ used ‘tell, don’t show’ to tell a political message about racism. That’s a good message! Some readers won’t notice a political message in their books if the message isn’t shoved down their throat. However, ‘show, don’t tell’ and ‘tell, don’t show’ are NOT mutually exclusive. An author trying to appeal to a broad audience will use BOTH ‘show don’t tell’ and ‘tell don’t show’ in their book, layering them together like an onion to provide more and more layers the closer you look at a book.

If I were to summarize my thoughts on this book, I’d say it’s good at critiquing history, as good as or better than anything else I’ve read in the genre. But the actual story going on here was a bit dull.

Did you like this critique/review? Here are some more: The Rest of My In Depth Reviews

On a personal note, I’m open to editing books. I don’t like putting myself out here like this, but I’ve been told I should. Check my blog for details if interested.